As part of our Meet the Team series, we introduce you to one of our UCSF Broad Stem Cell community members. Meet Elizabeth "Betsy" Crouch, MD, PhD, a neuroscientist, vascular biologist, and physician in neonatal-perinatal medicine. She offers a glimpse into her journey on the MD-PhD track, her experiences, and insights into how this dual degree offers unique perspectives.

Who should consider an MD-PhD?

I think many people are intimidated when they approach the idea of applying to an MD-PhD program because it is a big commitment. Here is how I advise students who are considering MD/PhD programs: practicing medicine is largely about the application of existing knowledge. As others have described, this is a highly refined skill and also requires intuition (the “art” of practicing medicine). It is a profound calling and certainly, you don’t also need a PhD to eventually perform research as a doctor. But MD/PhD programs protect your time at an early stage to equip you to push the boundaries of our existing knowledge and solve problems that require different types of skills to answer. You absolutely don’t have to know that you want to ultimately be a professor and run a lab to embark on an MD/PhD program. You just have to enjoy performing experiments and love the thrill of the chase: answers to unsolved questions.

While it takes many years to get both degrees, don't think about the time at the onset. Recognize that, if you enjoy what you're doing, those eight years will pass by quickly.

The other thing that people should know about doing an MD-PhD is that it is all paid for by the federal government and institutional support with some rare exceptions.

It was empowering to me, for example, in this era where there is a conscious effort to increase the representation of people of color and women in academia, to be able to go to an Ivy League school for my MD-PhD degrees for free. If it hadn't been fully funded, I would have been forced to take out a ton of loans or to turn down the opportunity altogether. It’s important to recognize how physician-scientists, in the end, will be poised to have unique insights into certain diseases because of the time that they've spent immersed in training in both medicine and how to ask scientific questions. Another reason MD-PhD training is a significant asset is that it strengthens your approach and eventual grant applications to be able draw on both skill sets. For example, I can position myself as, "I'm a clinician who sees babies/patients who have this disease, and I'm also a PhD trained neuroscientist who can design and execute the right experiments.” This combination is powerful. Even though you may be older than your PhD-only colleagues when you start a lab or become an attending physician, the lack of student loan burden and the benefit of a multi-angled lens was worthwhile at least for me.

How did you get to where you are today?

How this evolved for me personally is that during my PhD I knew I wanted to study neuroscience — it sounded like the new frontier. I had been studying immunology for two years after college. Immune cells are more accessible than brain tissue, both in animal models and in humans. This advantage has propelled immunology to thrilling technical innovation, more quickly than neuroscience. However, I wanted to go into something where it was more open, more unknown. I switched from immunology to neuroscience for my PhD. Now, I look at immunology that has, for example, CRISPR-related genetic therapies in juxtaposition with neuroscience where, in some instances, we are designing the basic, proof-of-concept experiments — I am a bit jealous knowing how far immunology has come. They’re both great fields!

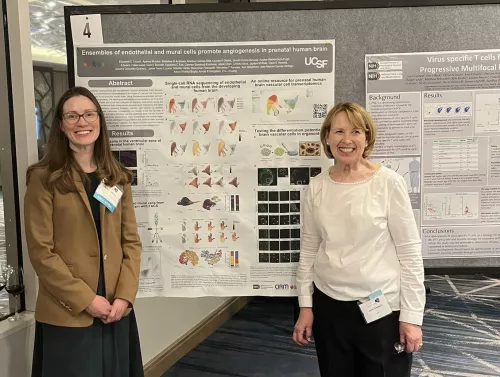

Doctorate Training — How neural stem cells interact with blood vessels

During my PhD, I looked at how neural stem cells interact with blood vessels. For a long time, blood vessels have been thought of as mere passive pipes — just delivering oxygen and nutrients. Now the paradigm has shifted: we're reconstructing blood vessels to think about them as signaling hubs. They sit between the blood and the brain parenchyma, and they communicate between these different types of cells using a variety of diverse mechanisms. They also of course create the blood-brain barrier which we are starting to deconstruct not as an impenetrable wall but instead as multiple carefully regulated gates. Beyond these roles, they also likely contribute to brain metabolism. My favorite topic is thinking about neurogenesis (the development of neural cells in the brain) and angiogenesis (the development of blood vessels) in the immature brain. These two processes are not only simultaneous but also interdependent and the consequences of germinal matrix hemorrhage in preterm babies are almost certainly an example of this mutual co-dependence.

Residency — Watching development as a pediatrician

I finished my MD-PhD training at Columbia and came to UCSF for my residency in pediatrics. It took me a little bit to decide I wanted to be a pediatrician but eventually, I realized that I like stem cells and development. As a pediatrician that's what you're doing — you're watching development in a human. And kids are delightful.

The most interesting time period of pediatrics to me was neonatology — taking care of premature babies who are sometimes born about halfway through pregnancy, so they are extremely immature. I soon realized that this unique window creates a special challenge: the neonatologist serves as a primary care doctor for the baby when they’re in the NICU. You need to be treating and balancing all of the different organ systems: the heart, lungs, GI tract, skin, kidneys, brain, etc. In addition, these systems are all at various stages of what is really stem cell biology and additionally should be developing in a very different environment. This creates challenges and opportunities that I enjoy solving in collaboration with both my MD colleagues and many of our other experts in the NICU: nurses and nurse practitioners, respiratory therapists, dieticians, and pharmacists.

Primarily, I am a neuroscientist. Out of all the systems, the immature brain is arguably the area where we still have the biggest knowledge gaps. Babies who are born so prematurely are still highly fragile, and the morbidity rates amongst those who survive are very high. This means that these babies, depending on their complications, may never walk or talk or be able to live independently and that's a significant commitment for those lifelong caregivers. This is an area where we need to make a lot of progress.

Brain Hemorrhages — Why the brain vasculature?

One of the major complications in these babies is brain hemorrhages, formally called germinal matrix hemorrhage., You might imagine that a lot of blood in the brain as those cells are developing is bad, and that's indeed the case. Babies who have this hemorrhage are at high risk of cerebral palsy and intellectual challenges. Unfortunately, we have no disease-modifying treatments for this condition and can only try to manage the bad consequences afterward. During my pediatrics residency, I was particularly struck when caring for a family whose baby had this brain hemorrhage. Together we went through a series of discussions to understand the baby’s prognosis. In a convicting way, the family was surprised we had no treatments. So, the family asked if there were any clinical trials for this disease? The answer was no. They asked if there were any experimental compounds? We actually don't have any of those either. And so, in the final discussion, the mom said if there's absolutely nothing for this disease, and my baby is never going to be able to walk or talk or even engage meaningfully with the world, we're going to donate her body to research.

I found this situation profoundly unsettling at that time and now. In the field of cancer, we have a range of therapeutic options to offer families—chemotherapeutic regimens and biological interventions that have been explored in other contexts. We can tailor these treatments based on the molecular profiles of the disease. However, when it comes to germinal matrix hemorrhage, we have nothing to provide in terms of effective interventions. This propelled me to try to profile the cells in the blood vessels of the human brain during my postdoctoral work. However, we were only able to get a snapshot of them in the second trimester, so our next step is to try to understand what those cells look like before and after the second trimester — How do they interact with the neurons in the brain? And how can we potentially think about modifying that interaction to prevent bleeding or limit the damage once it happens? I’m incredibly lucky to work on this problem at UCSF, especially in the environment of the Newborn Brain Research Institute, run by Dr. Xian Piao. We have a strong group of scientists all working on the special aspects of brain injury in the context of development, including Drs. Zena Vexler, Donna Ferriero, Fernando Gonzalez, and Mark Petersen. I’m inspired and helped by these generous and brilliant people frequently.

Clinical Practice — Aligning your passion and personality

For a while, I thought I wanted to be a pediatric neurologist, but there's an important part of your medical journey, which is figuring out whether there are aspects of the clinical practice that also match your personality and interests. Adult neurology now has some disease-modifying therapies that have come a long way thanks to a lot of great work at UCSF and other institutions. However, in pediatric neurology, many patients have genetic conditions or brain injuries that are static. While the field is evolving in exciting ways with clinical trials that deliver genetic therapies, the day-to-day practice of pediatric neurology has a large component of palliative care and managing the symptoms of children who are going to be very different than a typical child. Every person will fall uniquely on this spectrum, but I needed to be able to see my clinical decisions make an impact more immediately. And I’m impatient, so the sooner the better! For these reasons, I realized an intensive care environment was a better fit.

On a day-to-day basis as the neonatologist, you're the one who has to decide how to manage the patient from the moment when they are born and their intrauterine physiology changes drastically to the postnatal situation. We know 95% of germinal matrix hemorrhage happens within the first three days, so these decisions matter for long-term brain health. There were some groundbreaking studies at UCSF in the 70s looking at how to care for premature babies' lungs and the invention of a compound called surfactant. These days, a baby who's born after 30 gestational weeks has an excellent prognosis. The majority of what I do is take care of babies who are just born early, and thanks to some wonderful scientific and technological progress, should have an excellent long-term outcome. There are also interesting, challenging cases that stretch me, and many of these involve the brain, for example, germinal matrix hemorrhage, but also meningitis, stroke, and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. In that way, I still do a lot of neuroscience in my day-to-day clinical practice without being a neurologist.

Pediatric Research — Its current status and urgent need

Sallie Permar, MD, PhD, Pediatrician-in-Chief at Weill Cornell Medicine emphasizes that pediatric research is dramatically underfunded in this country. While I think there are some understandable reasons behind that — it's scary to experiment on children —there's a risk-benefit ratio that we can all accept as beneficial. Germinal Matrix Hemorrhage is a severe disease that causes a stroke as the blood pools in the ventricles, generating pressure that congests the veins causing a phenomenon called post-hemorrhagic infraction. I have been successful in applying for grants from the American Heart Association because they are interested in stroke and heart disease, and this specific type of stroke is under-studied. We need options for families whose babies have this condition in the future, and I’m very motivated by this goal.

Preterm Birth Initiative — Finding personal truth in focus groups

In 2020, I was awarded a grant from the Preterm Birth Initiative, a UCSF-funded organization interested in perinatal and prenatal complications. When first applying for this grant, the Initiative got back to me saying the science was fantastic, but they felt it needed more community involvement. As I had limited experience working with people, I reached out to my mentor, friend, and colleague, Dawn Gano, MD, MAS, a pediatric neurologist. She is also the clinical director of the UCSF Fetal Neurology Center of Excellence and is in touch with the communities of patients who are impacted by pediatric neurological disease. She recommended that I get in touch with Linda Franck, RN, PhD, FAAN, a professor of family health care nursing whose program of research focuses on health care for acutely and chronically ill infants and children in community and healthcare settings. Dr. Franck had connections with a support group for families experiencing a loss called “HAND” located in the Bay Area. We collaborated in conducting focus groups with parents recruited from HAND who wanted to talk about their experiences. We sought to understand how best to talk to families in this situation and share on the topic of performing research, especially with brain tissue.

What we found from those focus groups is that families want to contribute to research when it's proposed in a way that is supportive and it's part of the overall legacy planning for their baby. In the experience of profound loss, many families find that this possibility enables them to find meaning and provides them with a way to talk about their experiences. In fact, a mother told me that one of the most healing aspects of participating in research was that she got to say her son's name, as there were limited venues where she found she could talk freely about her experience.

The mother noted that it often makes people feel sad and awkward when she shares her experience, but she was able to talk about her son and about what his life meant to her in this new community, which provided her with many more conversations about otherwise unspoken experiences in a general setting. I found these focus group experiences and exchanges incredibly meaningful, and impactful. In fact, I see these focus groups as a strong call for action. If the parents who are in this situation want researchers to investigate and find therapies, it is critical that we respond.

Focus Groups — Uncovering perspectives on research engagement

In partnership with Mercedes Paredes, MD, PhD, a neurologist physician-scientist, and operating from the UCSF Broad Stem Cell Center, our team is enlisting the expertise of medical student Melissa Coloma to advance our collaborations with families to ask about THEIR research priorities. Specifically, we are collaborating with a cohort under the care of Dr. Adam Numis, whose research centers on epilepsy, and Dr. Shabnam Peyvandi, a UCSF cardiologist who studies the impact of congenital heart disease on brain development. Melissa’s discussions will revolve around questions such as Why did you participate in research? What were your impressions before and after research? This line of inquiry will be particularly focused on a subgroup of infants who faced a heightened risk of developing seizures or epilepsy during the neonatal period. We aim to delve into the motivations behind their decision to participate in research and explore their perceptions before and after their research involvement. Our overarching objective is to glean insights from the diverse array of individuals engaged in research, spanning both the scientific and community spheres. We recognize that various demographic groups carry unique perspectives and preconceptions, and our aim is to gain a deeper understanding of these attitudes and their potential impact. Ultimately, this endeavor seeks to pave the way for a more inclusive and diverse research landscape.

Exploring Ideas — Spiderman, doctors, and challenging stereotypes

It's intriguing to juxtapose the character of Spiderman with the concept of doctors being portrayed as villains, like Doc Ock, but with a twist—imagine a character like Doc Ock as a morally upright scientist. This idea invites us to reflect on public perceptions and the subtle messages that often shape our subconscious beliefs.

The recent TV series, "Manifest," features a female scientist named Saanvi Bahl as its central character. She embodies the archetype of a scientist as a force for good, challenging the prevailing stereotypes. In this narrative, we explore her character's journey, highlighting her positive impact on the world. I was delighted to see this representation, which contrasts with other depictions of scientists like the "Big Bang Theory." That cast was a tremendously talented group of people, but aren’t we all tired of the awkward white male scientist and the dumb attractive female dichotomy? We need to see more diverse representations, such as women and people of color, as accomplished scientists and socially adept humans! This portrayal also doesn’t encourage the public to engage with science. When Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, it captured the imagination of many different types of people. I would like to see our society return to a time when science was more accessible and captivating by non-scientists.